Tennessee has been in the news this year for our reading progress – well-deserved recognition for a smart strategy, well-executed. As states look for ways to improve reading outcomes, I believe the Tennessee model should be the Go To approach. Here’s why.

Tennessee hasn’t just trained teachers, we’ve given them the right tools: curriculum.

Teacher training has become increasingly-popular as a means to bring the Science of Reading into classrooms, for good reason. Tennessee didn’t forget this; our Reading360 initiative trained 30,000 Tennessee teachers over the last two summers, and our teachers have raved about the experience.

However, training isn’t enough. If you simply tell teachers what needs to change without giving them the tools to do it, you become that coach that yells, “Run” or “Tackle” on the sidelines, without providing the plays and the playbook required for success.

By 2019, the “Best for All” initiative ensured that all districts now use high-quality ELA curriculum. This has been a game-changer. Curriculum enables the changes we’ve asked teachers to make to be tangible and feasible. It is the proverbial playbook.

This is the cornerstone of our improvement, and the backbone for everything else that follows.

This curriculum focus stands in marked contrast to other states who’ve made a ‘Science of Reading’ investment; Mississippi has been rightfully cheered for its teacher training successes, but recent reporting reminds us that they are still catching up on bringing high-quality, knowledge-building curriculum to schools, to address the other aspects of the Science of Reading. Tennessee leads on literacy by investing in the Both-And of curriculum and training.

We are doing “curriculum-aligned professional learning” at statewide scale.

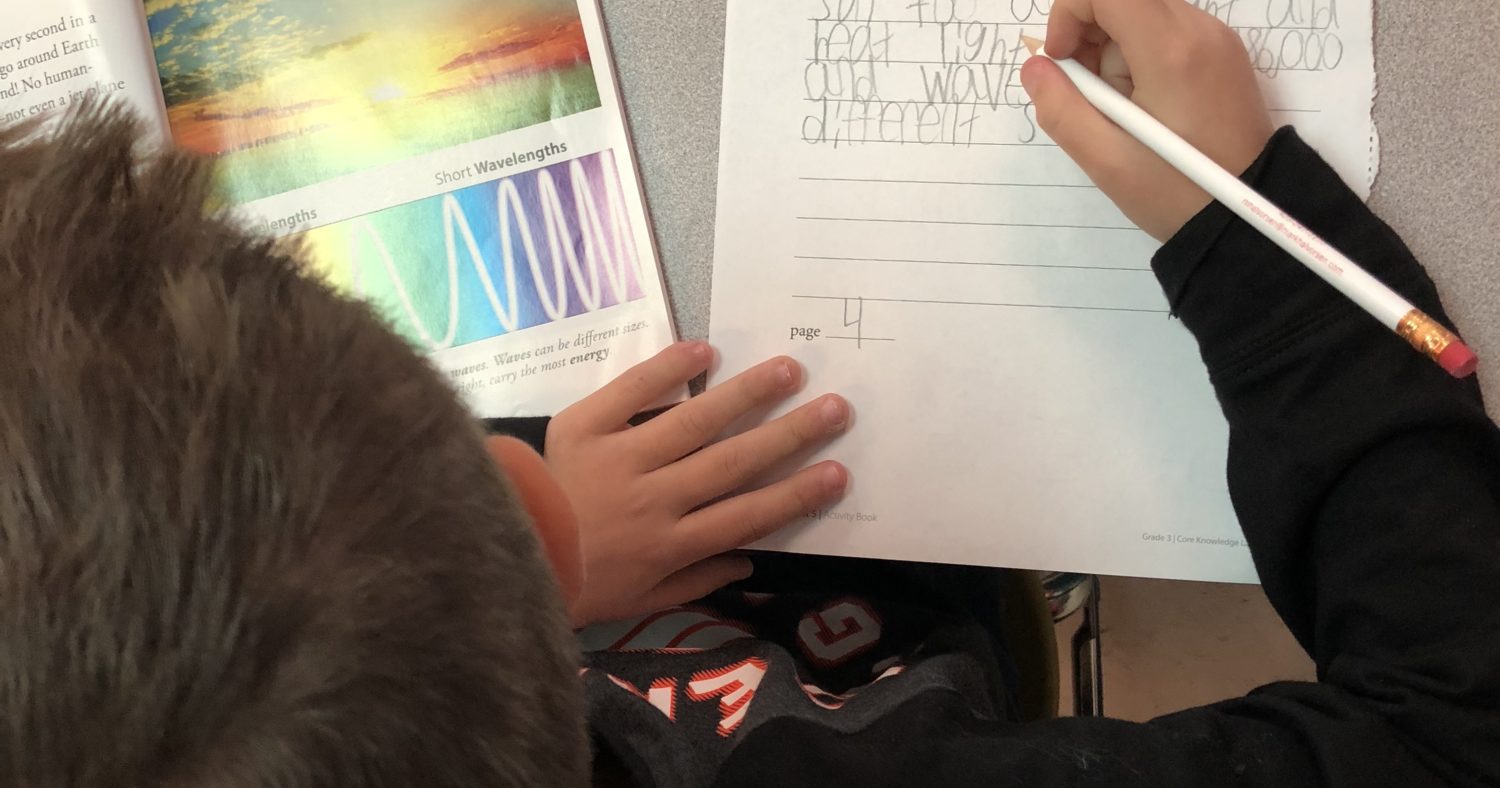

The Reading360 training was especially impactful because teachers had curriculum in hand during the training. The professional learning incorporated study of, and practice with, either the district-adopted foundational skills curriculum or the Tennessee Foundational Skills Curriculum Supplement – free, excellent materials developed by the state. Educators worked from the playbook, while learning why those plays were strategically essential. They weren’t just learning about why foundational skills matter, they were practicing classroom implementation. We can’t underestimate how much this makes the concepts more “real” to our teachers.

Education leaders talk about the need for professional learning to be curriculum-aligned, so that teachers have the playbook in hand as they are learning the concepts of the game. I consider #Reading360 training to be a proof of concept. Fortunately, this idea is getting traction nationally, and resources like Rivet Education’s Professional Learning Partner Guide have made it easier for districts to find partners for curriculum-based professional learning.

We aren’t just focused on foundational skills.

Foundational skills are critical, as we have seen firsthand in Sumner. So many of our kids were guessing at words, and we didn’t know it until we started using more rigorous curriculum and it exposed our foundational skills shortcomings.

Still, we knew that we had issues beyond the early grades. Our test results were OK in the lower elementary grades, but when our kids got into upper grades, things started trailing off.

But, since our shift to knowledge-building curriculum, we are seeing improvements that cross grades – something that is also reflected in Tennessee’s statewide testing results. Tennessee districts saw gains across K–12, with the strongest gains actually happening in high school. That’s an important proof-point for the knowledge-building approach, which really shines when cumulative learning is assessed.

Foundational skills are the easy (and important!) win; knowledge-building is harder Other states need to take note of Tennessee’s success.

We didn’t forget our secondary teachers.

When I taught high school history and English literature, I had students with so many reading needs, but no toolkit for dealing with them. I’m proud to be in a state that brought Science of Reading training to teachers in upper grades and across the content areas. This summer, Secondary Literacy training was unsurprisingly hailed by our teachers as incredibly beneficial. “I have felt pretty helpless until now,” said one 7th grade teacher, and boy could I relate.

Our investments in knowledge-building ELA curricula also gave essential tools to our upper grades teachers. Investing in the Science of Reading means more than success with decoding in K–2.

We didn’t just support teachers, we nurtured leaders.

Tennessee also supported Literacy Implementation Networks, in which districts across the state using common ELA curriculum are working with high-quality professional learning organizations to support implementation. Districts with mature implementations are partnered up with those that have newly adopted. These networks have been phenomenally successful, and the added benefit is that they’ve helped to create a collaborative culture, and shared experience, across the state around our literacy initiatives.

To my knowledge, Tennessee is the first state to truly scale curriculum-centered design for literacy. Keep an eye on our state in the years to come. With these investments taking root, I believe they will continue to bear fruit.