We have the honor and privilege of working in districts that have achieved meaningful literacy gains in recent years (more on that below). This work inspires us daily – and it would inspire you too, if you could see it.

Unfortunately, we’re unable to provide windows into our classrooms right now. One cost of this pandemic: the opportunity for site visits that can be invaluable to district leaders who’re making curriculum decisions.

We’ve often reflected on the importance of seeing – and showcasing – excellent ELA practice. You simply need to see this work with your own eyes to believe it.

We say so all the time, because of our firsthand experiences:

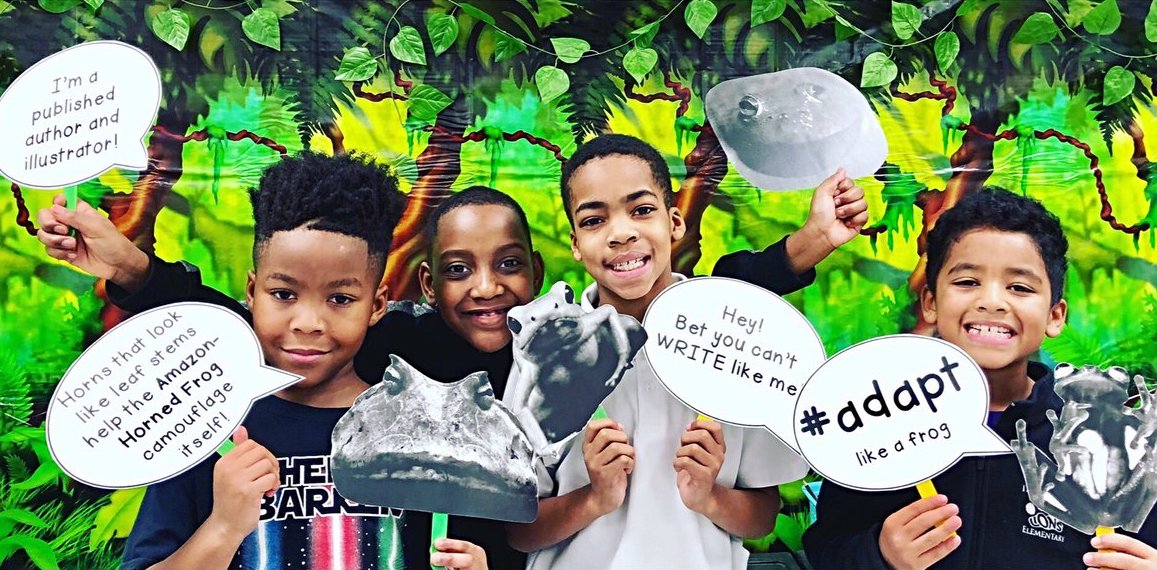

It can be hard to believe that students from different RTI tiers will be writing at the same caliber… until you see it with your K–2 students:

And with your 3–5 students:

Until you have seen kids beg their parents to come to ‘celebrations of learning’ to see their culminating projects, you won’t realize how exciting this is for the entire school community:

It can be difficult to appreciate how much the lack of curriculum costs teachers in prep time, including nights and weekends, until your teachers change curricula and quantify the time saved (10 hours per week!):

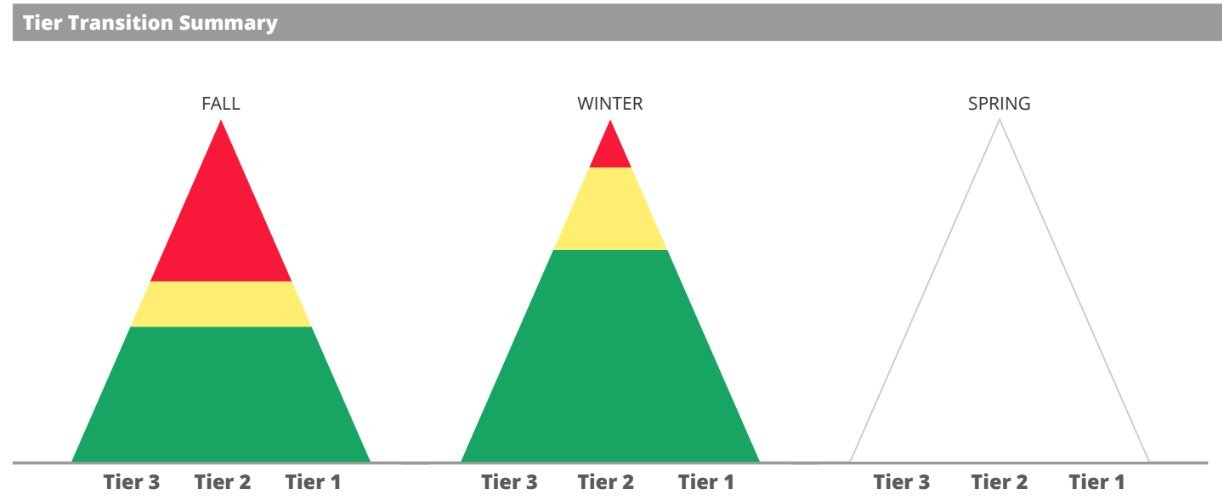

It can be hard to believe that you can move kids out of Tier 2 and 3 and into Tier 1 instruction in volumes… until you are watching it happen, in building after building:

And it’s practically unfathomable that teachers (who were once hesitant about new curricula) would make impassioned pleas to school boards to stick with a new curriculum – and then tweet their delight about curriculum adoption – until it happens:

Everyone doing this work with high quality curricula seems to echo this theme: You need to come see this work! Lauderdale County Superintendent Sean Kimble put it beautifully:

On top of all of the many disappointments this season, we’re lamenting the loss of a normal curriculum adoption season. Many Tennessee districts – and some beyond! – had planned to visit to see our work. We were excited by the idea that our #CurriculumMatters community would grow, and we could benefit from additional cross-district learning.

This blog is our attempt to give you a remote glimpse into our experience with high-quality ELA curricula – in lieu of the site visits we wish we were hosting.

Sharing Our Stories

We’ve been co-presenting about our work at Tennessee state convenings, and we’re pleased to share the presentation slides openly.

Here are a few highlights!

In Lenoir City, Millicent’s district:

Our first full year of implementation of EL Education nearly doubled our proficiency rates: from 12.9% before the curriculum to 24.3% after.

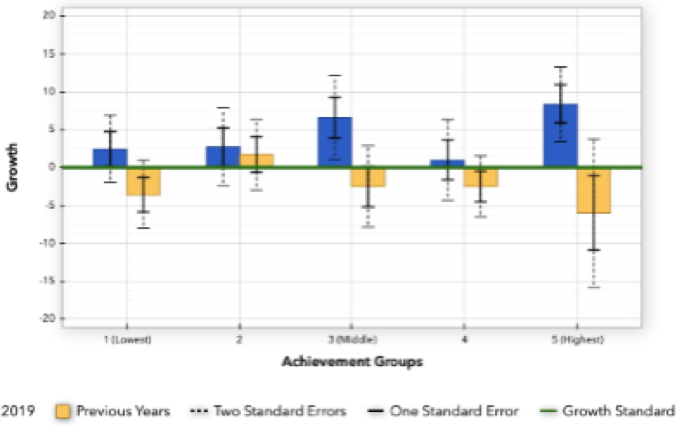

Best of all, every quintile of students grew:

We closed equity gaps, and saw historic levels of proficiency for our English Language Learners.

In Sullivan County, Robin’s district:

We have been steadily rolling out Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA) to new elementary grade levels over the past few years, and we really hit our stride last year.

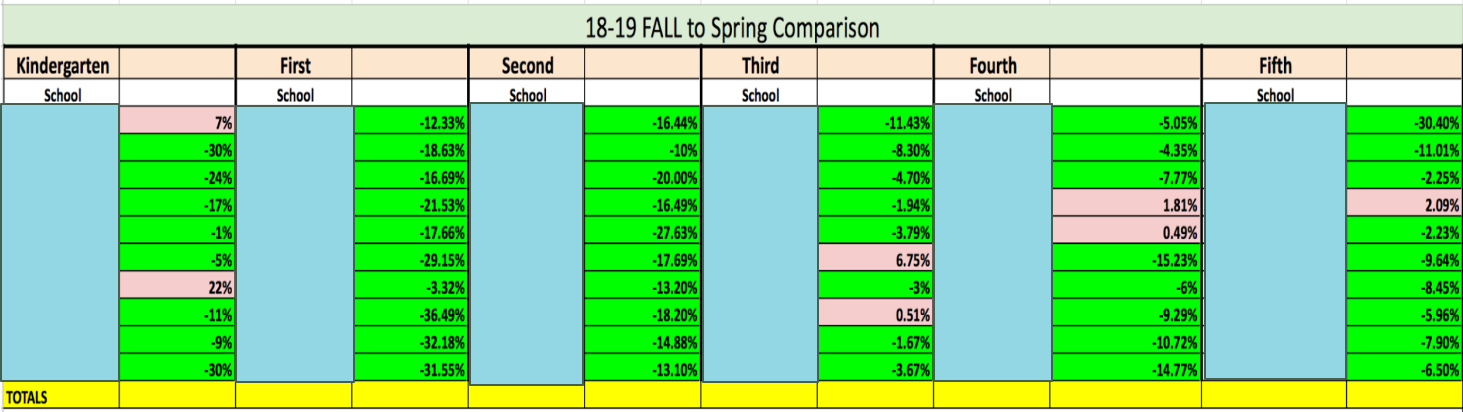

Not only did we decrease the number of students receiving Tier 2 and Tier 3 services last year, in every school (shown below, the Fall to Spring change):

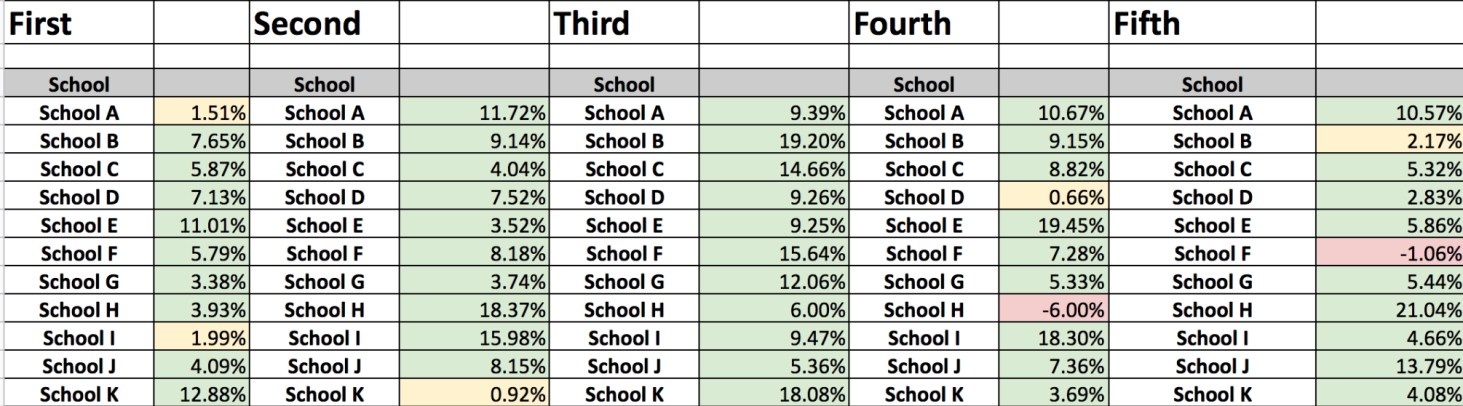

Across schools and grades, we also increased the number of students performing at the highest levels (at the 75th-100th percentile, when compared to national data)… here is our change in students at that top tier from Fall to Spring:

Please explore our slides (linked above) for more details.

You can hear more about our district journeys in The 74, where our colleagues have recently been featured for their work. Lenoir City Principal Brandee Hoglund shared her story of implementation success after a disappointing pilot. Sullivan County Principals Alesia Dinsmore and Angie Baker captured the shifts in ELA instruction in Sullivan County.

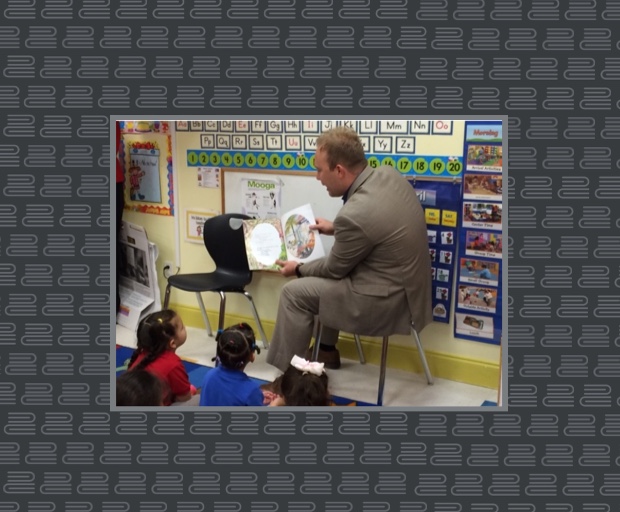

Also, the Knowledge Matters School Tour visited our classrooms, sharing many delightful insights and videos that capture our teams’ perspectives. Here is one of many examples:

Follow #KnowledgeMatters and #CurriculumMatters on Twitter for more of these shares!

An Important Note About Distance Learning

Let us tell you straight: Those curricula have been invaluable in our distance learning transition.

Lenoir City was able to take advantage of the free and open materials created for these curricula, including the Eureka Math on the Go lesson videos and the modEL Detroit resources created by Detroit Public Schools and EL Education; our implementation partner TNTP helped to develop stopgap lesson materials. In math, we used packets developed by ReadyMath in K-8; they developed Spanish-language materials, which was AMAZING. Our high school teachers are spending time with Illustrative Mathematics 9-12, a free, openly-licensed curriculum – in support of virtual learning to some extent, but mostly in preparation for next steps.

Sullivan County worked with our TNTP partner Kate Glover to provide high-quality literacy experiences for students at home, using the Core Knowledge curriculum. We also took advantage of free, open access to Amplify’s online products.

Fundamentally, having curriculum as a baseline made everything easier. Our teams are having enough of a challenge translating their lessons to distance learning formats… if they were still creating the lesson content each week, we cannot fathom how much harder this would be!

Our curriculum work has also given us a true north as we think about helping all kids access grade level work… even after this pandemic. We need to think less about meeting kids where they are, and more about accelerating their skills as we keep them on track with grade level work, just as we do today (both of our districts use curricula that get all kids working with worthy, grade level texts).

As Dan Weisberg and David Steiner recently reminded us, “Giving students lower-level work to help them catch up — or, in the more extreme version, asking them to repeat an entire grade — has good intentions and a certain logic. It’s also largely ineffective.” We’re glad to be part of a national community that is talking and thinking this way.

These experiences have increased our case for the investment in curricula that raised the bar in our schools – and gave us a national community of practice in the process.

___

Robin McClellan serves as Supervisor of Elementary Curriculum and Instruction for Sullivan County Schools in Blountville, Tennessee. Millicent Smith serves as the Supervisor of Instruction for Lenoir City Schools in Lenoir City, Tennessee.

We would both be open to sharing more about our work, and you can connect with us in Twitter; Millicent is here and Robin is here.